Past masters: 100 of the best pictures by British photographers since the 1920s

The writer William Boyd asks how, in an age of selfies, we are able to judge which images should endure

William Boyd FEBRUARY 21 2020

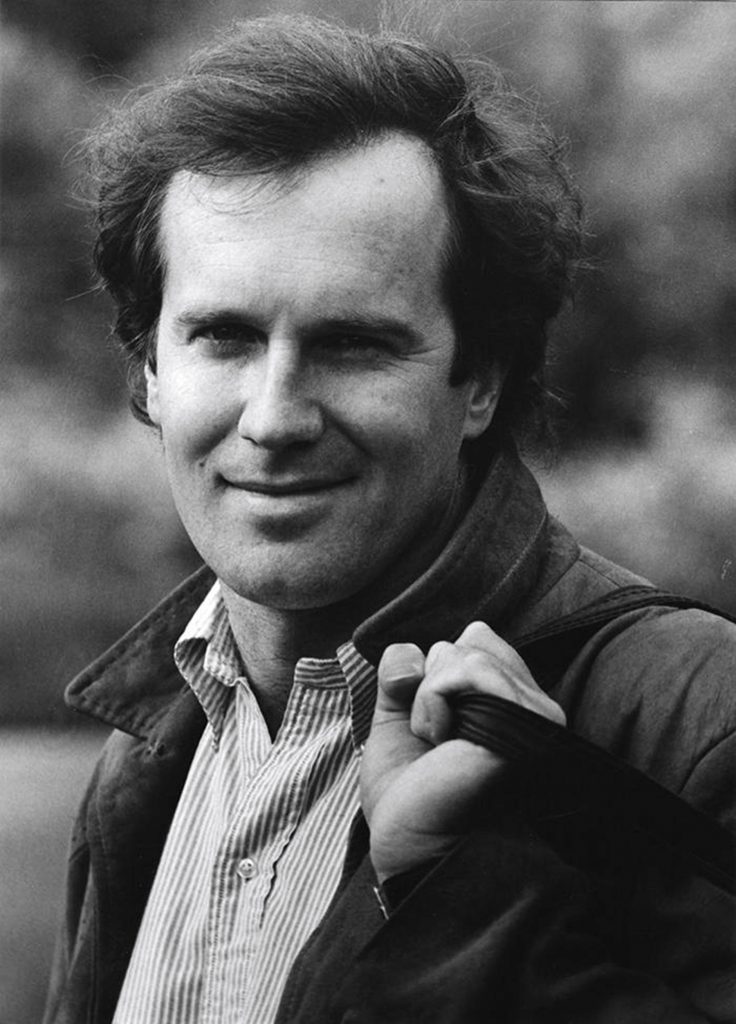

Back in the summer of 1982, I was living and working in Oxford but spending a lot of time in and around London, as the first film I had written was being shot for Channel 4 television. It was called Good and Bad at Games, a dark story of boarding school life (persecution and torture) and a subsequent bloody revenge.

One day, I went up to Totteridge, on London’s northernmost fringe, to a cricket ground where we were filming. There, I was greeted by our cinematographer, a kindly, elderly man (he was almost 70) who I knew as “Wolf”.

In one of the usual film-making delays, he asked if he might take my photograph. I said, yes, of course. He took out his camera and, in a few clicks, it was done. Later, Wolf sent me a print. That picture of my younger self (I was just 30) hangs in my study today.

I had no idea what a strange confluence of trajectories cohered in that apparently random Totteridge photograph in 1982. Wolf was, in fact, Wolfgang Suschitzky, something of a legend in the world of British photography.

He died in 2016, at the age of 104. He was born in Vienna in 1912 at the apogee of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and, in the 1930s, emigrated to England with his family. He, along with his sister, Edith Tudor-Hart (she had married an Englishman), were significant members of a potent émigré influence on British photography.

Some of Suschitzky’s early photographs now form part of a unique collection of British photography, the Hyman Collection. James and Claire Hyman (James, an art historian and gallerist; Claire, an oral surgeon) have assembled a large trove of photographs taken by British photographers in the 20th and 21st centuries.

It is a fascinating record of the art form as it pertains to the UK and, appropriately and challengingly, it poses some interesting questions.

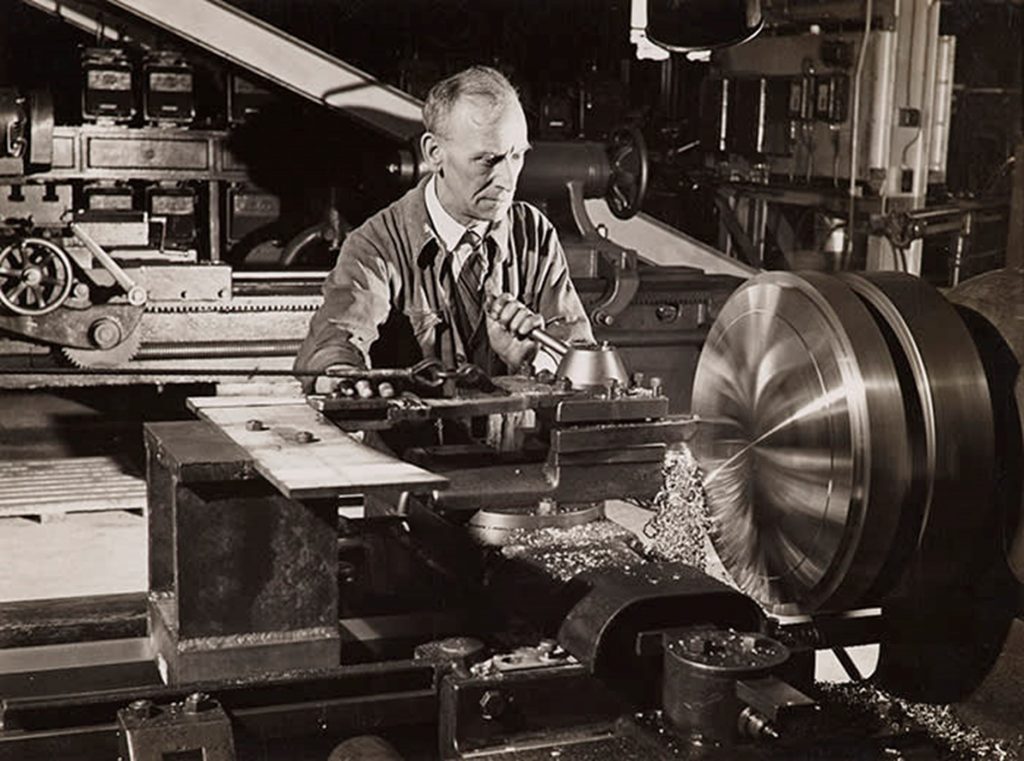

© Wolfgang Suschitzky

There are many potential histories of photography, as of any art form, even though photography, it’s worth restating, is a very young medium, with its origins only as far back as the middle of the 19th century.

Like film, it is something of an adolescent – not to say a child – in comparison with its rivals, the other six arts: literature, painting, music, theatre, sculpture and architecture. Its status as an art form – and its viability (some people will not even concede that it is an art) – is still somewhat in flux.

One history of photography is the technological one. When one thinks of Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) with her primitive sliding glass-plate cameras, their photosensitive chemicals and their interminable exposures, and then fast-forwards to today with the current plague of a trillion selfies, it’s easy to see how the medium has been transformed beyond recognition.

Photography is a mechanical method of reproducing an image (hence its derogatory appellation as “the artless art”) and every advance in camera and film manufacture, and now the digital manifestations, has changed the way photographs look and are taken.

Before the digital era, perhaps no technological advance was greater than the development of the portable 35mm camera (the Leica being the pre-eminent example in the 1920s). Suddenly, the snapshot was born.

Photography became the ultimate stop-time device. In a moment, an image could be seized and then reproduced in any size. Your camera fitted in your pocket. You didn’t need lights or a studio. The exposure speeds were in split-seconds. And so it has gone on.

The cheap box-camera, the Instamatic, motor-drives, electronic flash, the Polaroid and now the camera phone have all changed the art form irrevocably. Now everyone is a photographer, everyone carries a camera with them all the time. The number of photographic images proliferating is uncountable, limitless, overwhelming.

All of which makes the “old world” of analogue photography still more interesting and valuable. In a contemporary arena of trillions of images, how can we discern what is good and worth preserving?

Here is where archives and collections come into their own. Slow years of consensus have graded and judged these images as worthy and worth keeping. How did we get from there – to here? What can we learn?

There are histories of photography other than its technological development. One could consider the number of remarkable women photographers who have flourished over the century and a half of the form – Julia Margaret Cameron herself, Lotte Jacobi, Ilse Bing, Lee Miller, Marianne Breslauer, Margaret Bourke-White, Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman, amongst many others. Or the history of street photography – Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Saul Leiter, Vivian Maier.

Or the history of reportage – starting with Mathew Brady’s photographs of the American Civil War and moving on through Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, Weegee, Don McCullin, Philip Jones Griffiths, to Alastair Thain’s photographs of the Bosnian-Serbian war.

One could adduce a similar genealogical chain in the genres of portraiture (Nadar, Yousuf Karsh, David Bailey, Robert Mapplethorpe, Rankin) or artist-photographers (Edgar Degas, René Magritte, László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Nash, David Hockney). And so on.

These are all histories of great exemplars. Moreover, all these histories are transnational – no one country owns the genre.

You can’t posit a history of photographic reportage that belongs to, say, Spain in the way that you can discuss the development of Renaissance architecture in Italy, Russian music in the late 19th century or study French Impressionism in its purely French context.

Photography, the greatest democratic art form (all you need is a camera), seems very much an art sans frontières.

But here is the unspoken question – and ambition – behind the Hyman collection. Is there such a thing as a history of British photography? There are many great British photographers, for sure, but is there any discernible through-line that would allow us to see a tradition of photography that is quintessentially British?

The full Hyman collection assembles work by about 100 British photographers from the 1920s to the present day, from Cecil Beaton to Sam Taylor-Johnson, from Bill Brandt to Gillian Wearing. A selection of 100 photographs from this vast archive, curated by James and Claire Hyman, has recently been donated to the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, and can be viewed online in a display that illustrates the particular strengths of this national talent pool.

Of necessity, the Bodleian donation is highly selective. The 100 photographs have been taken by 18 photographers, approximately one-fifth of those in the wider collection, and the emphasis is heavily on portraiture and, unsurprisingly, Oxford undergraduate life.

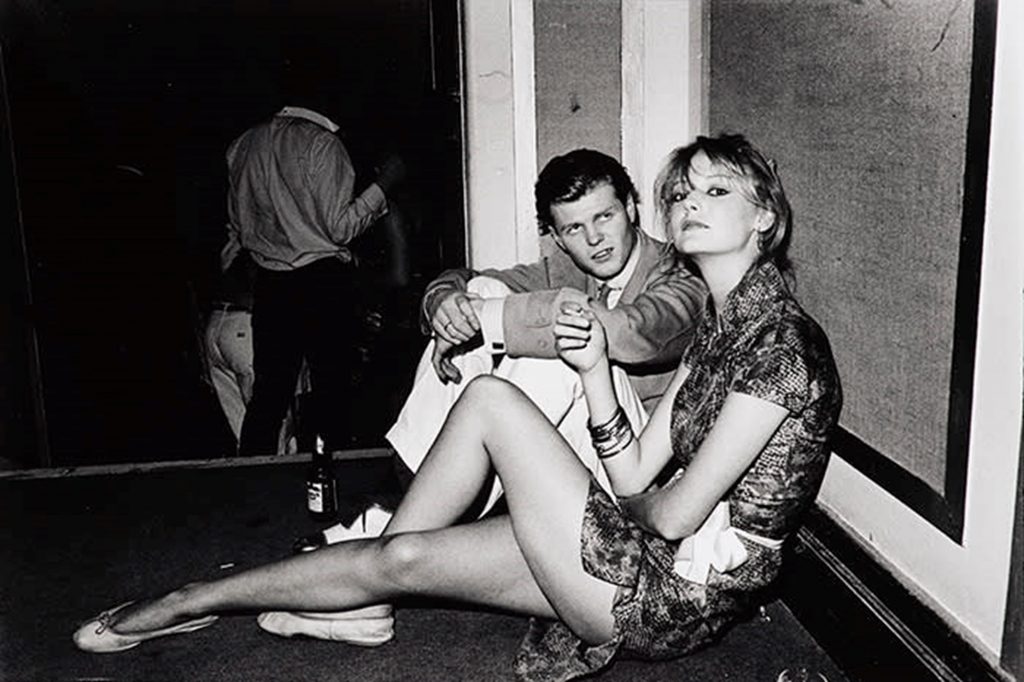

There are many Dafydd Jones photographs of gilded youth partying in the 1980s. But despite this redaction, the Bodleian donation does indicate the particular riches that British photography has to offer: it forms a pocket version, a microcosm, of what the larger Hyman collection preserves.

Sometimes, as the saying goes, you need to step back in order to see what is under your feet. Looking at the Hyman collection in all its generous circumambience, it is possible to pick out the broad outlines of a history of British photography. We can see that it came of age with the advent of the illustrated magazine in the 1920s and 1930s.

Just as Life magazine, Paris Match, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, Look, Vu and others heralded the dawn of photojournalism, with well-reproduced, authored photographs, so too in Britain came the era of Picture Post and to a lesser degree the Illustrated London News and Lilliput.

Suddenly the photographer’s byline was on a par with the journalist’s and the new standards of photographic excellence were set by the pages of glossy images in these publications.

The Hyman collection contains many of these Picture Post celebrity photographers, notably those by Kurt Hutton (real name Kurt Hübschmann), who emigrated to Britain from Germany in the 1930s. And it was this new demand for photojournalism coupled with outsider talent that shaped the next phase of British photography.

Edith Tudor-Hart and Wolfgang Suschitzky (Viennese), Bill Brandt (born in Hamburg) and Tom Blau (born in Berlin), coming from a continental Europe in turmoil and jeopardy, injected something fresh and lasting into the British photographic psyche.

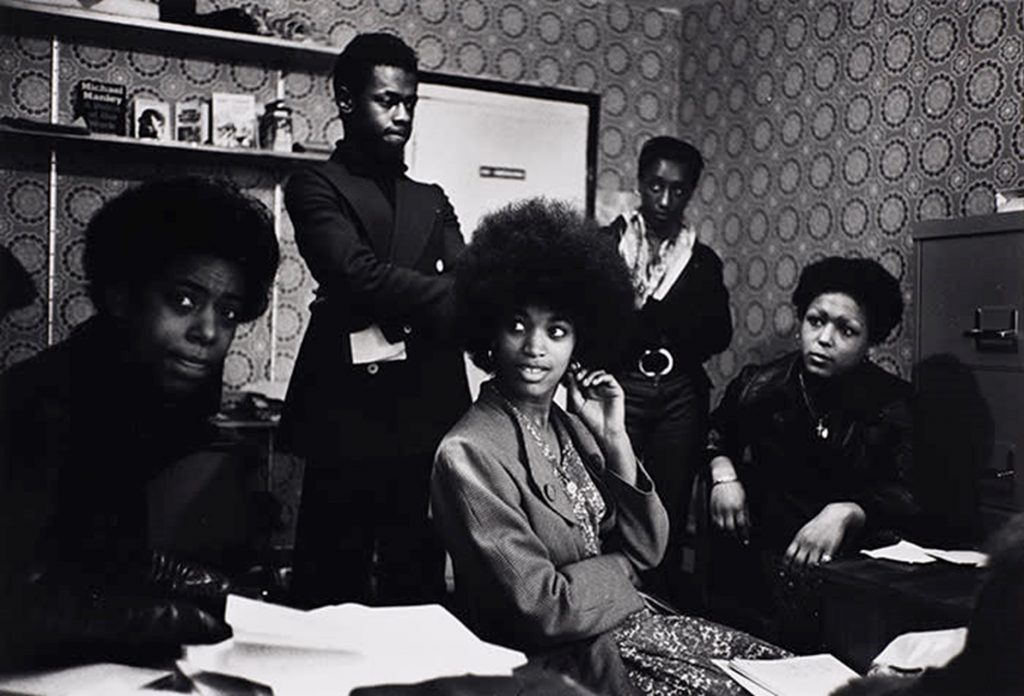

The early photojournalism of Picture Post and its peers was widely popular, but the images were often posed and unnatural. Created more as tableaux to illustrate a theme, often sentimental or whimsical, they were in opposition to the starker naturalism that these foreign photographers sought and practised. Yet slowly but surely this form of social realism came to dominate British photography, and is still evident in the work of Dafydd Jones and Martin Parr, for example.

Their photographs stand in a direct line from the photojournalism of the 1930s, and such a tone and mood has been a prominent feature of British photography ever since. Bert Hardy, Colin Jones and John Deakin are also faithful exponents of this clear-eyed observation. Don McCullin’s earliest photographs of East End gangs – before he went to war, as it were – were exactly in this vein.

The portrait was the other strong line in British photography that was generated by the explosion of photojournalism in the 1930s. Cecil Beaton, Tom Blau, Mark Gerson, Jane Bown, David Bailey, Lord Snowdon, Bob Carlos Clarke, Steve Pyke – the list of great British portrait photographers is a long one.

What is striking is a fundamental quality of candour and naturalism – and not glamorous, retouched puffery – about serious British portraiture that is a clear offshoot of the dominance of photographic social realism of the 1930s.

These observations, of course, are inevitably generalisations. Trying to discern wider cultural movements and artistic practices always demands some form of broad overview rather than specificity.

But it seems to me, surveying the hundreds of images in the Hyman collection, that if there is a commonality of style and spirit in British photography of the last century, it’s to be found in this concentration on the gritty, documentary aspect of the image being taken – its supposed truth – whether in reportage, landscape or the portrait.

A conception of the photographer as a demotic, disinterested, reliable witness seems to colour and pervade the photographs that British, or adopted British, photographers took and take today. On this evidence, we may indeed be justified in discovering a particular tradition of British photography, after all, and in the Hyman collection its values are fascinatingly enshrined and illustrated.

William Boyd’s new novel, “Trio”, will be published in October. The Hyman donation can be viewed at digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk